Peter Bengtsen: Blu a Bologna. Danni collaterali

La foto in alto è di Michele Lapini e documenta il muro del Centro sociale XM24 a Bologna, ricoperto l’11 marzo 2016 di vernice grigia da Blu e collaboratori

A due settimane dall’apertura della mostra Street Art – Banksy & Co. L’arte allo stato urbano (18 marzo – 26 giugno 2016) Carla Caprioli ha rivolto alcune domande a Peter Bengtsen, storico dell’arte e sociologo.

Nel 2014 Bengtsen ha pubblicato una monografia dal titolo The Street Art World, in cui presenta i risultati di una ricerca quadriennale presso il Dipartimento di Storia dell’Arte e Studi dell’Università di Lund, in Svezia (cfr. anche la recensione dello storico Joe Austin).

Nello stesso anno tiene una serie di conferenze e interventi sulla street art e ‘lo spazio pubblico come sito da esplorare’ (public space as a site of exploration), tra cui due presentazioni allo Stavanger’s NUART festival e al Museo dell’Hermitage di Leningrado.

Il mese scorso Bengtsen ha pubblicato il capitolo “Stealing from the public: the value of street art taken from the street” (‘Rubare al pubblico: il valore della street art tolta dalla strada’) nel volume collettivo The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art (2016, a cura di Jeffrey Ian Ross). Nel capitolo si discute lo status (e la sorte commerciale) delle opere di street art tolte dal sito originario, come pure alcuni argomenti a favore e contro la preservazione della street art.

La versione originale inglese di questo articolo è riportata alla fine del testo italiano.

Contesto

Per una sintesi in inglese dei recenti eventi relative alla mostra a Bologna si veda l’articolo di Michele Smargiassi in La Repubblica (12.03.2016), il post nel blog Giap gestito dal collettivo Wu Ming (12.03.2016) e l’articolo di Giovanni Vimercati su The Guardian (17.03.2016). Un elenco aggiornato di articoli in lingua inglese è reperibile con una ricerca su Google.

L’11 marzo 2016 l’artista italiano Blu ha ricoperto di vernice grigia tutti i murales che aveva prodotto nel corso di vent’anni nella città di Bologna. L’azione è stata intrapresa in risposta al distacco di alcune sue opere dai muri di Bologna da parte dell’équipe di un progetto museale locale, Genus Bononiae , ai fini di esporle alla mostra “Street Art – Banksy & Co. L’arte allo stato urbano” (18 marzo – 26 giugno 2016) nella sede di Palazzo Pepoli.

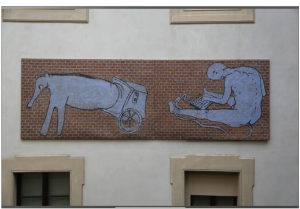

Murale di Blu in via della Liberazione, Bologna (foto per gentile concessione di rokus2000 – Ron Roelandt)

Il murale staccato ed esposto a Palazzo Pepoli (foto: Dailybest - © 2016 DAILYBEST by BetterDays srl)

I curatori della mostra sono Christian Omodeo e Luca Ciancabilla (esperto di restauro di affreschi), affiancati da Sean Corcoran (curatore per il MCNY, che ha portato la collezione di graffiti Martin Wong come ‘mostra nella mostra’). Il presidente del progetto Genus Bononiae è Fabio Roversi Monaco, presidente dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna e in passato (1985-2000) rettore dell’Università di Bologna.

In merito alla decisione di ricoprire di grigio i propri murales, Blu ha pubblicato una dichiarazione sul proprio sito “MAGNATE MAGNATI – a bologna non c’è più blu e non ci sarà più finché i magnati magneranno – per ringraziamenti o lamentele sapete a chi rivolgervi.” Tra i murales ricoperti di grigio, anche quello noto come ‘OccupyMordor’, realizzato nel 2013 sul muro del centro sociale ‘XM24’, come elemento di una campagna intesa a salvare il centro sociale dallo sgombero e l’edificio dalla demolizione.

Il murale realizzato da Blu nel 2013 sul muro dell’ XM24 (banner realizzato per la campagna http://ilovexm24.indivia.net/).

video: Wu Ming racconta Blu, OccupyMordor (16 aprile 2013)

[youtube]https://youtu.be/l2Xr4E2aQOM[/youtube]

Blu cancella i suoi murales a Bologna (16 marzo 2016)

[youtube]https://youtu.be/rWy3VlNyqN0[/youtube]

Di tale murale è stato conservato dall’autore solo un frammento che raffigura un altro centro sociale, ‘Atlantide’ (sgomberato il 21 ottobre 2014).

Frammento del murale di Blu che raffigura il centro sociale ‘Atlantide’ (dettaglio dell’immagine precedente)

Il distacco di alcuni dei murales di Blu per l’allestimento della mostra “Street Art – Banksy & Co. L’arte allo stato urbano” era già iniziato nell’inverno 2015, innescando un dibattito sulla stampa, in particolare sul periodico Artribune (ad es., sugli scopi della mostra, da parte di uno dei curatori, Christian Omodeo, e sugli aspetti giuridici, dell’avvocatessa Raffaella Pellegrino).

Christian Omodeo, uno dei tre curatori della mostra, è stato promotore del progetto ‘Le Grand Jeu’ a Parigi, in cui si era richiesto ad artisti di graffiti e street art di creare opera all’interno dell’edificio dismesso “Tour Paris 13”. In un’intervista (in inglese) rilasciata nel 2014 in occasione della StrokeArtFair, Omodeo descrive la sua nuova concezione di ‘art entertainment’: ‘from art to art entertainment’. Si veda anche l’intervista rilasciata a Giada Pellicari per StreetArtAttack in 2012.

In risposta alle critiche mosse alla mostra, Fabio Roversi Monaco ha dichiarato che i murales distaccati erano gestiti da una cooperativa senza fini di lucro appositamente creata, e che ne era prevista la donazione al comune di Bologna. Tuttavia il 19 marzo il sindaco di Bologna, Virginio Merola, ha espresso dubbi sull’opportunità di accettare la donazione, citando l’Eneide: “Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes”.

Altre polemiche riguardano la denuncia per imbrattamento a tre attivisti del centro sociale Crash, che hanno aiutato Blu a ricoprire i murales di vernice grigia. La loro situazione è paragonata a quella della recente condanna per imbrattamento (con 800 euro di multa) della street artist Alice Pasquini (AliCè), che venne denunciata dalla polizia municipale di Bologna nel 2013 per aver dipinto vari murales in zona universitaria. Un altro dibattito riguarda il fascicolo trasmesso dai vigili urbani in Procura, relativo al murales cancellato da Blu presso il Quartiere Savena, in via Lombardia, commissionato nel 2007 e pagato dal Quartiere con fattura (circa 1400 euro).

Non è la prima volta che Blu sacrifica le proprie opere. Nel dicembre 2014, a Berlino, Blu e Lutz Henze, co-autore e curatore di un progetto di street art, ricoprirono di vernice nera due grandi murales creati nel 2008 (Kreuzberg, Cuvrystraße). Lutz Henke scrive che il gesto è “un segnale d’allarme per la città e i suoi abitanti , un richiamo alla necessità di preservare spazi di opportunità accessibili ed animati, invece di produrre tassidermie d’arte zombificate”.

Intervista a Peter Bengtsen

D.

Nel tuo ultimo scritto, il capitolo del libro dedicato alla rimozione e al commercio di opere di street art, citi il film di Alfonso Cuarón ‘Children of Men’ (2006): nella hall del museo ‘Arca delle Arti’, in cui sono preservate le più importanti opere mondiali, è esposto un frammento di muro coll’opera di Banksy’s ‘Kissing Coppers’.

Dal film ‘Children of Men’, la scena della hall con l’opera di Banksy ‘Kissing Coppers’ (riprodotto dal sito http://urbanartassociation.com/)

E osservi che, mentre nel 2006 “l’idea che un’opera di street art potesse un giorno essere preservata ed esposta in questo modo sembrava quasi comica”, negli anni successivi “la prassi di rimuovere, preservare ed esporre opere di street art è divenuta sempre più comune”. Tuttavia, in sintonia con i commenti al film espressi da Slavoj Žižek’s, concludi che “Le opera di street art tolte dalla strada sono private del loro contesto, risultano completamente prive di senso”. E aggiungi che, dato che le opere di street art “sono di per sè site-specific, il passaggio al contesto museale è suscettibile di alterare in modo significativo il modo in cui vengono percepite”.

Puoi commentare brevemente i recenti eventi a Bologna? Esistono alternative all’atto di ‘rubare al pubblico’?

R.

Sono del parere che il distacco delle opere di Blu per poterle inserire in una mostra istituzionale sia problematico, ma del tutto prevedibile. Nel mio libro The Street Art World (2014) ho descritto il crescente numero di rimozioni di opere di street art e il commercio che ne deriva. Anche se a quanto pare, almeno per ora, gli oggetti esposti a Palazzo Pepoli non sono destinati al mercato, sono pur sempre stati rimossi dal sito originario e immessi in un contesto istituzionale. Indipentemente dal fatto che restino nelle mani di una fondazione, o siano donati alla città, tale cambiamento di contesto esercita un impatto significativo sulla modalità di fruizione di tali opere. Inoltre, il trasferimento delle opere ad un contesto istituzionale può influire sulla tipologia di utenza che riesce a fruire dei dipinti.

Per maggior chiarezza vorrei sottolineare che, dal punto di vista dello storico dell’arte, l’atto del preservare opere di street art presenta sia problemi sia potenziali vantaggi. La parafrasi dei commenti di Žižek alla fine del mio capitolo in The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art riflette l’atteggiamento dominante nei confronti della rimozione di opere e delle opere rimosse che ho riscontrato nel corso della mia ricerca, nei galleristi, negli autori di opere di street art e negli appassionati di questo genere. Per ora, si tende ad etichettare le opere rimosse come ‘rubate al pubblico’, indipendentemente dalla legalità o meno del processo di rimozione.

Per quanto riguarda la preservazione materiale di singole opere di street art, tutte le possibili alternative comportano problemi. Preservare le opere nel loro sito originale presenta in certa misura il rischio di fossilizzare il sito, potenzialmente impedendo l’emergere di nuove opere. D’altro canto, la rimozione decontestualizza opere essenzialmente site-specific, privandole di parte del loro significato. La prassi di rimuovere in vista di preservare può inoltre scoraggiare alcuni artisti dal continuare a creare opere in strada. La documentazione visiva (ad es., foto e video) delle opere in situ sembra essere la forma di preservazione meno invasiva, ma ovviamente con questo procedimento viene a mancare gran parte delle proprietà materiali delle opere.

Si deve osservare che la nozione della necessità di preservazione materiale presuppone che le singole opere siano importanti e debbano essere conservate per la posterità. In alternativa, invece di concentrarsi sulle singole opere, vale forse la pena di considerare l’importanza del processo in corso – il movimento sociale e artistico di cui le opere fanno parte. In tale ottica, la preservazione materiale delle opere può divenire irrilevante, perché l’azione artistica non si è mai focalizzata sull’opera materiale in sé. Invece di tagliare muri per preservare piccoli istanti nel tempo, un approccio più consono all’ethos della street art potrebbe consistere nell’osservare – e consentire – il passare del tempo e nell’accettare che le singole opere non siano destinate a restare.

In un’intervista ad Artribune, il co-curatore della mostra di Bologna Christian Omodeo afferma che il vero problema, quando si parla di arte urbana, “è piuttosto come faranno gli artisti a gestire i rapporti con i curatori” ed è persuaso che “un dialogo tra artisti e curatori urbani non [sia] solo necessario, ma fondamentale per gli anni a venire”. Reputo piuttosto interessante il modo in cui Omodeo colloca gli artisti e i curatori in queste due frasi. Omodeo sembra suggerire che sono gli artisti che devono venire a patti con la presenza, le idee e le ambizioni personali dei curatori. Di fronte a una posizione di questo genere, la mia domanda immediata sarebbe: perché?

Nel caso specifico di Blu: perchè l’artista, che a quanto pare non desidera che i curatori e le istituzioni si approprino delle sue opere di street art, dovrebbe instaurare un dialogo in merito? Purtroppo, se ci si basa su ciò che è accaduto a Bologna, la risposta potrebbe essere che se gli artisti rifiutano di entrare in dialogo o di conformarsi ai piani dei curatori, questi ultimi semplicemente andranno avanti e faranno ciò che vogliono. Devo ribadire che non conosco quale genere di comunicazione si sia instaurata tra Blu e i curatori prima della rimozione degli oggetti che sono ora in mostra a Palazzo Pepoli, ma reputo che le azioni dei curatori in questo caso abbiano lasciato ben poco spazio all’avvio di un dialogo autentico – a meno che le rimozioni ad opera della fondazione, e la successiva ricopertura di pittura grigia delle opere restanti in città da parte dell’artista, non debbano considerarsi una forma di dialogo non verbale.

Non voglio dire che i curatori non possano potenzialmente svolgere un ruolo quando si tratta di street art. Però, porsi in antagonismo con gli ambienti culturali che costituiscono il substrato dell’arte che si desidera proteggere non è forse la migliore soluzione, come si evidenzia dai danni collaterali che la mostra ha causato alle opere di street art che era possibile vedere a Bologna.

Come commento finale, vale la pena di ripetere che le opere di street art derivano molto del loro significato dal contesto in cui sono collocate. I dipinti ora in mostra a Palazzo Pepoli possono essere stati creati da Blu. Tuttavia, in quanto opere d’arte site-specific, si può sostenere che una volta che gli oggetti vengano tolti dal sito originario, non possano più essere considerati opere d’arte. Aggiungerei che ciò è particolarmente vero nel caso in cui un artista vivente espressamente affermi di essere contrario alla rimozione di un’opera site-specific dal suo contesto originario. (Per approndimenti sull’importanza del sito, cfr. anche il mio contributo “Site Specificity and Street Art” nell’antologia Theorizing Visual Studies. Writing Through the Discipline – 2013).

D.

Il mese scorso, in un’intervista rilasciata a StreetArtNYC, affermi che “i teorici che tentano di ‘analizzare’ la street art […] sono ancora oggi visti come una sorta di ‘avvoltoi intellettuali’ che si gettano, per impadronirsene, sui resti di un ambiente sociale e culturale di cui conoscono ben poco”. E prosegui dicendo che “hai visto ricercatori fallire nel loro lavoro perché mancava loro una comprensione di base delle regole sociali dell’ambito che tentavano di studiare”. Analogamente Jeffrey Ian Ross, curatore de The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art (2016), sottolinea che gli attuali studi teorici sui graffiti e la street art lasciano molto a desiderare.

In quest’ottica, e sulla base della tua esperienza personale, puoi citare organismi che promuovano queste competenze?

R.

Ciò riporta ad una problematica più vasta, relativa alla formazione e all’etica della ricerca. A mio parere, un fattore che rende complessa la ricerca sui graffiti e la street art, è la molteplicità e la diversità delle discipline teoriche che se ne occupano: ne deriva che le prassi e gli standard di etica della ricerca risultano molto disparati. Un recente esempio è la pubblicazione di uno studio di profilazione geografica che esplicitamente nomina una persona che gli autori reputano sia l’artista Banksy. Gli autori hanno inserito il nome nella pubblicazione accademica anche se riconoscono apertamente che non possiedono alcuna prova conclusiva a sostegno di tale identificazione. Sul piano etico, ciò mi sembra molto problematico. Ciò può ovviamente avere conseguenze per la persona citata nell’articolo. Può anche rendere molto più difficile il lavoro di altri ricercatori del settore, perché a quel punto si tratterà di convincere i protagonisti del mondo della street art che si possono fidare di loro, e che non scriveranno alcunchè di sensazionale per aumentare il numero di lettori.

Da quanto mi risulta, non vi sono organismi che si occupano di problemi etici nel campo dei graffiti e alla street art. Il dr. Samuell Merrill all’Università di Umeå, in Svezia, insieme a me e ad altri studiosi dei graffiti e della street art provenienti da vari paesi, ha avviato un progetto che potrebbe contribuire a istituire un codice di condotta etica. Ma anche se questo progetto viene realizzato, non significa che tutti i ricercatori vi aderiranno.

Un altro segnale in direzione di un fruttuoso dibattito nel campo dell’etica è il crescente numero di conferenze accademiche dedicate specificamente alla street art e ai graffiti. Un esempio è The Lisbon Street Art & Urban Creativity International Conference , un forum di discussione di prassi etiche connesse alla ricerca sui graffiti e la street art. Nel giugno prossimo presenterò un contributo a questa conferenza, dedicato all’articolo di profilazione geografica che ho citato.

D.

Nell’aprile 2015 a Bologna, nell’ambito di un ciclo di conferenze dell’Accademia Clementina, Luca Ciancabilla – uno dei co-curatori dell’attuale mostra di Genius Bononiae – tenne insieme a Marco Dugato un seminario su “Graffiti tra arte e diritto. Quali confini”. Roversi Monaco, attuale presidente del progetto Genius Bononiae, contribuì alla sessione di presentazione. Ciancabilla espresse il suo apprezzamento per i murales di Blu, comparati per importanza a quelli di Michelangelo: “hanno fatto cambiare volto alla città, facendola diventare una metropoli di respiro internazionale” e che “vanno protetti”. Roversi Monaco dichiarò alla stampa: “C’è bisogno di alternative alla sottocultura degli ultimi anni” (cfr. rassegna stampa). Tuttavia in tale occasione, per ‘ragioni riservatezza’, essi non dettero alcun dettaglio della futura mostra di street art.

Come rilevato in un commento inviato da Flipx al blog Giap, ciò è in forte contrasto con quanto avveniva a Bologna negli anni Settanta, quando le autorità locali cercavano il dibattito con le istituzioni artistiche e l’Università sui temi legati all’arte contemporanea nel contesto urbano. Nel post si ricorda che nel 1977 il Comune di Bologna, l’Accademia di Belle Arti e l’Accademia Clementina organizzarono insieme una serie di conferenze sul tema “Perché continuiamo a fare e a insegnare arte?” In tale occasione Umberto Eco, uno degli oratori, dichiarò che “fare arte è una pratica che distrugge paradigmi”. E, secondo lo storico dell’arte Renato Barilli: “l’operatore estetico non sarà più un produttore di oggetti che entrano nel circuito della merce, ma diventerà una specie di animatore, di allenatore della superficie estetica della comunità”. (Perché continuiamo a fare e a insegnare arte? a cura di Luciano Anceschi. Cappelli, Bologna, 1977).

Esistono modelli o buone prassi di governance da applicare nei casi in cui una comunità deve affrontare problemi legati alla produzione e alla gestione dell’arte, ai regimi di visibilità dello spazio artistico e dello spazio pubblico?

R.

Intanto vorrei precisare che l’idea che l’”operatore estetico” – o artista – non sia necessariamente un produttore di oggetti corrisponde perfettamente a quanto sottolineavo prima, quando dicevo che bisognerebbe concentrarsi sul processo e sul contesto più ampi di cui l’artefatto fa parte, piuttosto che sul singolo elemento di street art quale oggetto che può essere preservato.

Per quanto concerne la governance, è importante comprendere che lo status della street art si è sostanzialmente modificato nell’ultimo decennio. Le opere di street art non sono più considerate vandalismi, ma sempre più come beni culturali legittimi donati ad una comunità. Di conseguenza, nella percezione di molti cittadini tali opere sono divenute di proprietà e di responsabilità comune. Ciò si rileva ad esempio quando dei volontari di una comunità lavorano insieme per restaurare opere di street art sfigurate. Questi casi indicano che la street art può rientrare nella tradizione dell’estetica relazionale, operando come catalizzatore dell’interazione sociale. Sono convinto che la capacità di raggiungere il pubblico negli ambienti quotidiani e di creare un senso di comunità positivo sia una caratteristica importante della street art, che non può essere preservato quando si trasferiscono le opere in un contesto istituzionale, al difuori del contesto quodiano della comunità.

Dato il coinvolgimento della comunità, quando si tratta di gestire le opere reputo importante mantenere il massimo grado di apertura. Ciò che abbiamo visto finora, è che i singoli operatori (ad esempio: ladri, proprietari degli immobili, galleristi e curatori) hanno ‘estratto’ le opere senza preoccuparsi di ottenere il consenso degli artisti e della comunità in cui le opere sono collocate, né quantomeno di consultarli.

Capisco che i vari mondi, della politica artistica, istituzionale e curatoriale, non sempre consentono un’apertura totale. Tuttavia, se in futuro un curatore desidera ‘estrarre’ delle opere, dovrebbe conformarsi al principio di un dialogo autentico ed aperto sia con gli artisti sia con le comunità, anche se tale dialogo dovesse condurre ad un risultato diverso da quello auspicato dal curatore. Senza dubbio ciò renderà più difficile il compito del curatore, ma potrà anche contribuire a prevenire altri tipi di ricadute, quali la copertura con vernice grigia delle restanti opere di Blu. Anche se non vi sono ostacoli giuridici alla rimozione di un’opera di street art dal suo sito originario, reputo che l’episodio di Bologna abbia chiarito perfettamente l’importanza del principio di trasparenza: come risultato diretto di una decisione curatoriale, consistente a) nel non consultare l’artista a proposito delle rimozioni delle opere, oppure b) nell’ignorare il punto di vista dell’artista in materia, molte comunità cittadine hanno ora perso opere d’arte per loro importanti.

D.

Nei tuoi scritti citi il “potenziale della street art di aprire lo spazio pubblico e trasformarlo in un sito da esplorare”. Ciò, come affermi, non è in contraddizione con il crescente numero di festival di street art, che a loro volta agevolano la produzione di opere di grandi dimensioni effettuate su commissione. Un recente esempio è il grande murale dell’artista italiano Ericailcane, prodotto a Sassari con il contributo dell’assessorato alla cultura locale.

Puoi fare qualche commento sulle opere di street art prodotte su commissione, e sulle loro specificità?

R.

Ciò che descrivo come ‘potenziale della street art di trasformare lo spazio pubblico in un sito da esplorare’ è in stretta relazione con la natura aperta, non autorizzata ed effimera della street art. Il fatto che la street art sia aperta significa che, in linea di principio, chiunque può parteciparvi, ad esempio creando nuove opere o modificando quelle esistenti in strada. Il fatto che sia non autorizzata significa che le opere autorizzate, create su commissione, non ricadono all’interno della mia abituale definizione di street art. Devo precisare che quando parlo della natura non autorizzata della street art, mi riferisco non tanto ad uno status effettivo, quando ad una status percepito: spesso il passante non è in grado di determinare se un’opera è stata o meno autorizzata. Pertanto, ciò che è importante è la percezione dello status dell’opera, e le opere di street art più facilmente percepite come non autorizzate non sono i grandi murales, ma quelle di minori dimensioni. Il fatto che la street art non sia autorizzata è fortemente connesso al fatto che è effimera. Dato che la street art non dovrebbe effettivamente trovarsi dov’è, è spesso rimossa o sostituita con qualcos’altro in un lasso di tempo relativamente breve, oppure subisce col tempo l’effetto degli eventi atmosferici.

I murales prodotti su commissione hanno un effetto diverso. Come si è detto, i grandi murales, che siano o meno effettuati su commissione, danno solitamente l’impressione di essere autorizzati e di carattere permanente. Inoltre, date le dimensioni, non sono così facilmente soggetti ad alterazioni come le opere di street art di minori dimensioni.

Il carattere aperto, non autorizzato ed effimero della street art è importante perché crea un senso di urgenza nello spettatore.

Un incontro inaspettato con un’opera percepita come qualcosa che non dovrebbe in effetti trovarsi lì (e che potrebbe scomparire o modificarsi in breve tempo) ha la potenzialità di farci uscire dalla routine quotidiana e aumentare la nostra consapevolezza di quanto ci circonda. Questa creazione di consapevolezza è in sostanza ciò che intendo quando affermo che la street art ha il potenziale di trasformare lo spazio pubblico in un sito da esplorare. È un’esperienza molto più difficile da conseguire con i murales permanenti di grandi dimensioni.

Ciò non significa che io non apprezzi i murali di grandi dimensioni effettuati su commissione. Molti di essi, compresi quelli prodotti in concomitanza con festival di street art, sono opere di grande valore, che però non operano allo stesso modo di quella che io chiamo street art.

Blu in Bologna: collateral damages. Interview with Peter Bengtsen, art historian and sociologist

In the wake of the recent opening of the exhibition “Street Art – Banksy & Co. L’arte allo stato urbano” (March 18th – June 26th, 2016), Carla Caprioli asks some questions to art historian and sociologist Peter Bengtsen.

In 2014, Bengtsen published a monograph entitled The Street Art World, the result of a four-year research project carried out at the Division of Art History and Visual Studies at Lund University, Sweden (see also a review by historian Joe Austin).

The same year he gave a number of talks about street art and public space as a site of exploration, including presentations at Stavanger’s NUART festival and the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. He also recently published the chapter “Stealing from the public: the value of street art taken from the street” in The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art (edited by Jeffrey Ian Ross, 2016). The chapter discusses the status (and commercial fate) of removed street artworks as well as some of the arguments for and against the preservation of street art.

Background

For a summary in English of the recent events surrounding the exhibition in Bologna, we refer to an article by Michele Smargiassi in La Repubblica (12.03.2016), a post in blog Giap run by collective Wu Ming (12.03.2016) and an article by Giovanni Vimercati in The Guardian (17.03.2016). An updated list of articles in English can be found on Google.

On March 11th 2016 the Italian street artist Blu covered with grey paint all his murals in Bologna, which had been painted during a span of 20 years. This action was an answer to the removal of some of his artworks by a local museum project, Genus Bononiae, for the purpose of the exhibit “Street Art – Banksy & Co. L’arte allo stato urbano” (March 18th – June 26th, 2016) on the premises of Palazzo Pepoli.

Blu’s mural removed and shown at Palazzo Pepoli (photo courtesy of Dailybest - © 2016 DAILYBEST by BetterDays srl)

The exhibition’s curators are Christian Omodeo, Luca Ciancabilla (expert of frescoes restoration) and Sean Corcoran (curator for the MCNY, who brought to Genius Bononiae the Martin Wong graffiti collection as ‘an exhibit in the exhibit’). The president of the Genus Bononiae project is Fabio Roversi Monaco, president of the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna and former Rector (1985-2000) of the University of Bologna.

Blu released a statement on his website regarding the decision to paint over his own work:“ MAKE MONEY TYCOONS – There’s no more Blu in Bologna, and there will be no more as long as tycoons make money; for thanks or complaints you know whom to turn to.” Among the grey-covered murals is one known as ‘OccupyMordor’, produced in 2013 on the wall of the social space ‘XM24’ as an element of a campaign intended to save the social space from eviction and the building from demolition.

The ‘OccupyMordor” mural produced by Blu in 2013 on the wall of the social space ‘XM24’. (banner produced for the campaign, courtesy http://ilovexm24.indivia.net/)

video: Wu Ming illustrates the mural OccupyMordor by Blu (April 16, 2013)

[youtube]https://youtu.be/l2Xr4E2aQOM[/youtube]

video: Blu erases his murales in Bologna (March 16, 2016)

[youtube]https://youtu.be/rWy3VlNyqN0[/youtube]

Of this mural, only one fragment was kept, representing another social space, ‘Atlantide’ (evicted on October 21th, 2014).

The detachment of some of Blu’s murals to allow their inclusion in “Street Art – Banksy & Co. L’arte allo stato urbano” had already started in Winter 2015, raising a debate in the press, particularly in the magazine Artribune (e.g. on the exhibit’s motivations by co-curator Christian Omodeo and on legal aspects by lawyer Raffaella Pellegrino).

Co-curator Omodeo is the promoter of project ‘Le Grand Jeu’ in Paris, where street and graffiti artists have been asked to work inside the dismissed building “Tour Paris 13”. See an interview in English given in 2014 at the StrokeArtFair, where Omodeo describes his ‘new conception of art entertainment’: ‘from art to art entertainment’. See also a skype interview given to Giada Pellicari for StreetArtAttack in 2012.

To answer criticism to the exhibition, Fabio Roversi Monaco declared that the detached street artworks were managed by a non-profit co-operative created for this purpose and would be donated to the municipality of Bologna. However, on March 19th Virginio Merola, current mayor of Bologna, expressed doubts about the opportunity of this donation, quoting the Aeneids: “Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes” (“Beware the Greeks even if they bear gifts”).

Parallel debates concern three members of the social space ‘Crash’ who helped Blu in covering the murals with grey paint, and who are now being sued for damages. Their situation is being compared to the street artist AliCè, who was sued for damages for producing murals in Bologna and recently sentenced to pay a fine of 800 euros; another debate concerns a file forwarded to the prosecutor by the Bologna municipal police, concerning the murals recently grey-painted by Blu in the local Savena District, via Lombardia, which had been commissioned by the District in 2007 and paid upon invoice (some 1,400 euros).

This is not the first time Blu has destroyed his own work. In December 2014, in Berlin, he and co-creator/curator Lutz Henke covered with black paint two murals created in 2008 (Kreuzberg, Cuvrystraße). Lutz Henke wrote that the action was intended “as a wake-up call to the city and its dwellers, a reminder of the necessity to preserve affordable and lively spaces of possibility, instead of producing undead taxidermies of art”.

Interview with Peter Bengtsen

Q.

In your recent book chapter on the removal and trade in street artworks, you mention the movie ‘Children of Men’ (2006, dir. Alfonso Cuarón) in which an ‘Ark of the Arts’ museum project – rescuing the most important artworks of the world – exhibits in its entrance hall a big wall fragment with Banksy’s ‘Kissing Coppers’.

‘Children of Men’: museum hall with Banksy ‘Kissing Coppers’ (image via http://urbanartassociation.com/)

While, in 2006, as you state, “the idea that removed street artworks might one day be preserved and displayed in this manner seemed almost comical” in the years since the release of the film “the practice of removing, preserving and exhibiting street artworks has become increasingly commonplace”. However, in tune with Slavoj Žižek’s comments on the movie, you conclude that “Street artworks removed from the street are deprived of their context, they are totally meaningless”. You also point out that since street artworks “are in essence site-specific, the shift to the context of the museum may significantly alter how the artworks are perceived”.

Can you briefly comment on the recent events in Bologna? Are there alternatives to the act of ‘stealing from the public’?

A.

The removal of BLU’s artworks for the purpose of an institutional exhibition is, to my eyes, problematic, but by no means unexpected. In my book The Street Art World (2014), I have written about the increasing number of removals and the subsequent trade in artworks from the street. While it seems that – at least for now – the objects on display at Palazzo Pepoli are not meant to go on the market, they are still being taken from their original site and put in an institutional context. Whether they remain in the hands of a foundation or are eventually donated to the city, this change of context has a significant impact on the way the paintings are experienced. In addition, the displacement to an institutional context may affect who gets to see the paintings.

For clarity, I would like to stress that as an art historian I see both problems and potential advantages with the preservation of street artworks. The paraphrasing of Žižek at the end of the chapter in The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art reflects the dominant attitude towards removals and removed artworks I have found in the art market and among street artists and street art enthusiasts during my research. For the moment being, there remains a strong discourse that labels removed artworks as stolen from the public, regardless of the legality of the extractions.

When it comes to the material preservation of individual street artworks, all the viable alternatives I can see entail problems. Preserving street artworks in their original context to some degree runs the risk of fossilising the site, potentially preventing new artworks from emerging. Removal, conversely, decontextualises essentially site-specific artworks, thereby depriving them of a significant part of their meaning. Removals with a view to preserve may also discourage some artists from continuing to put up their work in the street. Visual documentation (e.g. photography and videography) of artworks on site seems to be the least invasive form of preservation, but of course the material properties of the artworks are largely lost with this process.

It should be noted that the perceived need for material preservation presupposes that individual artworks are important and should be kept for posterity. As an alternative to this point of view, rather than focusing on individual artworks, it is perhaps worth considering the importance of the ongoing process – the social and artistic movement – the artworks are part of. From such a perspective, the material preservation of the artwork may become irrelevant, because the material artwork itself was never the artistic point. Rather than cutting out walls to preserve little moments in time, it might be a more fitting approach in line with the ethos of street art to look at, and allow for, the passing of time and accept that the individual artworks are not meant to keep.

In an interview in Artribune, co-curator of the Bologna exhibition Christian Omodeo says that the real problem when discussing urban art is “how artists will manage relationships with editors” and that he believes “a dialogue between artists and urban curators is not only necessary, but critical in the years to come”. I find the order in which Omodeo places artists and curators in these two sentences in the interview rather interesting. His formulations seem to suggest that it is the artists that have to come to terms with the presence, ideas and, significantly, the personal ambitions of curators. My immediate question to this stance would be: why?

In the specific case of Blu, why should the artist, who apparently does not wish to see his street work appropriated by curators and institutions, enter into a dialogue about the issue? Sadly, from what has transpired in Bologna, the answer might be that if artists refuse to enter into a dialogue, or if they refuse to consent to the curators’ plans, the curators will simply go ahead and do whatever they want anyway. I should stress that I don’t know what communication has taken place between Blu and the curators prior to the removals of the objects that are now on display at Palazzo Pepoli, but I believe the actions of the curators in this case have left very little base for any genuine dialogue going forward – unless the removals by the foundation and the subsequent white-washing by the artist of the remaining artworks in the city is to be considered a form of non-verbal dialogue.

I do not mean to say that curators cannot potentially play a role when it comes to street art. However, antagonising the cultural environments that are the nexus of the art one wants to protect is probably not the best way to go, as evidenced by the collateral damage the exhibition has caused to the street art viewable in Bologna.

As a final comment to this question, it is worth reiterating that street artworks get a lot of their meaning from their context. The paintings now on display at Palazzo Pepoli may have been created by Blu. However, as site-specific works of art, once they are taken out of their original site it can be argued that the removed objects are no longer to be considered artworks at all. I would say that this is especially true when a living artist expressively states that he is against the removal of a site-specific artwork from its original context. (For more thoughts on the importance of site, see the chapter “Site Specificity and Street Art” in the anthology Theorizing Visual Studies. Writing Through the Discipline (2013)).

Q.

Last Month, in an interview with StreetArtNYC, you stated that “academics that are seen to attempt ‘investigating’ street art […] are sometimes still looked upon as a species of ‘culture vulture’, swooping in to pick the bones of a social and cultural environment they know little about”. And you continue that you “have seen researchers fail in their work because they lacked a fundamental understanding of the social rules of the field they were trying to study.” Similarly, Jeffrey Ian Ross, editor of The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art (2016), points out that there is a lot of room for improvement when it comes to the academic study of graffiti and street art.

In this perspective, and on the basis of your own experience, can you mention entities promoting these competences?

A.

To a large degree, this really comes down to a broader question about training and research ethics. I think one challenge with graffiti and street art research is that the field is being approached from so many different academic disciplines that research practices and standards for research ethics will inevitably vary. One example is a recently published geographic profiling study, which mentions by name a person the authors believe to be Banksy. The authors have included the name in their published academic article even though they acknowledge directly in the text that they have no conclusive evidence to back up the claim about Banksy’s identity. Ethically I find this highly problematic. It may of course have consequences for the person mentioned in the article. It may also prove to make more difficult the work of other researchers within the field, as they will now have to convince people within the street art world that they can be trusted to maintain the integrity of their contacts and not write sensationalist pieces to increase their readership.

As far as I am aware, there are currently no formal entities that focus on the specific ethical issues related to researching graffiti and street art. Dr. Samuell Merrill at Umeå University, along with myself and a number of other international street art and graffiti scholars, are working on a project that might contribute to establishing a code of ethical conduct. However, even if this project comes to fruition, it does not mean that all researchers will adhere to it.

Another hope for a fruitful ethical debate is the increasing number of academic conferences that focus solely on street art and graffiti. The Lisbon Street Art & Urban Creativity International Conference is one example of a forum where ethical practices related to street art and graffiti research may be discussed. Later this year, for example, I will be presenting a paper at the conference on the issues with the abovementioned article on geographic profiling.

Q.

In April 2015, in the framework of a series of conferences organised by the Accademia Clementina in Bologna, one of the Genius Bononiae exhibition’s co-curators, Luca Ciancabilla (together with Marco Dugato) held a seminar on “Graffiti between Art and the Law. Which borders?”. Roversi Monaco, the current president of the Genius Bononiae project, contributed to the welcome address. Ciancabilla expressed his appreciation for Blu’s murals, which he compared to Michelangelo’s: “they have changed the face of the city, transforming it into a contemporary metropolis” and “should be protected”. Roversi Monaco told the press that “we need an alternative to the subculture that has reigned in Bologna in recent years” (for both statements, see press cuts). However, as both recently stated, on that occasion – for ‘confidentiality reasons’ – they did not disclose the details of the future street art exhibition.

As was remarked in a comment by Flipx in the Giap blog, this is in stark contrast with what happened in Bologna in the 1970s, when local authorities actively promoted a debate with art institutions and the University on issues related to contemporary art in the urban context. The commentator recalls that in 1977 the Municipality of Bologna, the Academy of Fine Arts and the Accademia Clementina co-organised a series of conferences on the theme ‘Why do we still produce and why do we still teach art?” On that occasion Umberto Eco declared that “making art is a practice that destroys paradigms”. And according to art historian Renato Barilli: “the aesthetic operator will be no longer a producer of objects to be put into the circuit of goods, rather a kind of facilitator, a coach of the aesthetic side of the community” (In Perché continuiamo a fare e a insegnare arte? Ed. Luciano Anceschi. Cappelli, Bologna, 1977).

Are there models or good practices of governance to be applied by a community when dealing with art production and art management, and the visibility regimes of art space and public space?

A.

Let me begin by noting that the idea that the “aesthetic operator” – or artist – is not necessarily the producer of objects corresponds very well with the point I wanted to make when I said previously that focus should perhaps be on the larger process and context the artwork is a part of rather than the individual street artwork as an object that can be preserved.

With regards to governance, it is important to understand that the status of street art has changed significantly in the last decade. Rather than vandalism, it has become increasingly common for street artworks to be seen as gifts for – and legitimate cultural assets to – a community. As a result, many citizens feel a sense of communal ownership and obligation towards the artworks. This can for example be seen when volunteers from a community work together to restore street artworks that have been defaced. Such cases indicate that street art may inscribe itself in the tradition of relational aesthetics, working as a catalyst for social interaction. I believe the ability to reach people in their everyday environments and to create a positive sense of community is an important artistic trait of street art, which cannot be preserved when moving artworks out of the everyday environment of the community and into an institutional setting.

Given the community attachment, I think it is important to maintain as much openness as possible in relation to handling the artworks. What we have typically seen so far is that single agents (e.g. thieves, building owners, art dealers and curators) have extracted artworks without obtaining consent from – or at least consulting – the artists and the community in which the artworks are placed.

I understand that the politics of the art institutional and curatorial worlds do not always allow for complete openness. However, if a curator in the future wishes to extract artworks, it should be a governing principle to do so in a genuine and open dialogue with both artists and communities, even if such a dialogue might lead to a different outcome than what the curator would have liked. There is little doubt this will make the curator’s task more difficult, but it may also help prevent the kind of fallout we have seen with the white-washing of Blu’s remaining artworks. Even if there are no legal obstacles to removing a street artwork from its original site, I think the importance of the principle of transparency has been made very clear by what has happened in Bologna: as a direct result of a curatorial decision to either a) not consult the artist about the removals or b) ignore his views on the matter, many communities in the city have now lost artworks that were important to them.

Q.

In your works, you mention “street art’s potential to open up public space and turn it into a site of exploration”. This, as you state, is not in contradiction with the growing number of street art festivals and commissioned large-scale artworks they facilitate the production of. A recent example is the mural produced in Sassari by artist Ericailcane, supported by the local municipality (Department of Culture).

Can you briefly comment on the issue of commissioned street artworks and their specificities?

A.

What I call street art’s potential to turn public space into a site of exploration is heavily dependent on the open, unsanctioned and ephemeral nature of street art. That street art is open means that in principle anyone can participate, for example by creating new work or by modifying existing artworks on the street. That it is unsanctioned means that artworks created with permission fall outside of my usual definition of street art. It should be noted that when I talk about the unsanctioned nature of street art, I am referring to a perceived rather than an actual state: it is often not possible for the casual passerby to determine whether or not an artwork has been made with permission. It must therefore be the perceived status of the artwork that is important, and smaller street artworks are generally more likely to be interpreted as unsanctioned than larger murals. That street art is unsanctioned is strongly connected to it being ephemeral. Because street art is not really meant to be there in the first place, it is often removed or replaced with something else in a relatively short time span or it is affected by the elements over time.

Commissioned murals work differently. As mentioned, large-scale murals, whether commissioned or not, will typically give the impression that they are sanctioned and of a relatively permanent nature. Also, because of their scale, they are not as readily open to alteration in the same way as smaller street artworks.

The open, unsanctioned and ephemeral nature of street art is important because it creates a sense of urgency in the spectator.

An unexpected encounter with an artwork that is experienced as something that should not really be there (and might be gone or changed soon) can potentially pull us out of our everyday routine and increase our awareness of our surroundings. This creation of awareness is in essence what I mean when I say that street art has the potential to turn public space into a site of exploration. It is an experience that is much harder to achieve with large-scale, semi-permanent murals.

It is important to make clear that this does not mean that I dislike large-scale, commissioned murals. Many of them, including those commissioned in connection with street art festivals, are great. It is just that they work in a different way than what I call street art.

Category: Arte e Poesia, Osservatorio sulle città, Video